A Look at the November 2019 LSAT

- by

- Dec 23, 2019

- LSAT

- Reviewed by: Matt Riley

Interrupting everyone’s holiday festivities, scores for the November 2019 LSAT were released last Thursday. These scores brought holiday joy to some (those who were satisfied with their scores; LSAT instructor dorks, such as yours truly, who get a shiny new LSAT to play with) and despair to others (those who were decidedly less than satisfied with their scores; those same LSAT instructor dorks who have to translate their thoughts on the exam into lengthy blog posts). But whether this exam wrought good or bad tidings, we’re going to go over it, as we do following the release of every published LSAT. So let’s get to some quick hits on the November exam …

• Following most LSATs, there’s an early and near-universal consensus on what was the hardest part of the exam. Think the so-called “flower game” following the September 2019 exam. No so for the November test. Some thought the passage on peptides and microchips was the most dyspeptic. Some thought the last game on representatives from various companies represented the greatest challenge. Still others threw up their hands and declared the whole thing difficult.

For me at least, I thought the final game was the most difficult part of this exam. That game involved the scheduling of four representatives’ visits to factories in the three far-flung countries of France, Ghana, and India. We call these games “repeat” tiered ordering games; we had to schedule the order of the visitations three separate times (requiring us to “repeat” the ordering process three times, essentially).

Except there was a major twist in this game — representatives could visit some factories more than once over the four-month span. In most of these “repeat” tiered ordering games, each player goes exactly once each time you order the players. On this game, each representative could go as many as three times or as few as zero times each time you ordered them. Which meant there was a lot more to keep track of as you worked through the game.

As with almost any game though, a bit of work upfront made things more manageable. There was a pretty straightforward way to make two scenarios, each of which filled out part of your set up. These answered a few of the questions. There was also a pretty important — but difficult to make — deduction regarding the distribution of players to each country. Partly because players who visited the factory in France could not also visit the factory in India (one can apparently see both London and France, but not Mumbai and France, according to the dictates of this game), there were only four possible distribution of players to France and India. Trying to answer the remaining questions without having determined these distributions would have exposed you (and your underpants).

• Speaking of games, the major theme of this set was players being underbooked — which is our way of saying that the games gives you fewer players than places to put those players. We, presciently, noted this trend before this exam, and even predicted that there would be an underbooked game on this test. Before we get too self-satisfied, however, we should note that this wasn’t the most inspired prediction — nearly every recent published test included at least one underbooked game.

But even we weren’t ready for this set of games, in which three of the four games were underbooked. Aside from the company representative game we discussed above (in which four players had to fill twelve slots in your set-up), the first game (in which five agents had to schedule a meeting over seven months) and the third game (in which five technicians had to be divided into three two-person groups) were underbooked as well. Aside from some tricky language in the first game (which relied on the distinction between being the third agent to go versus going in the third month, for instance — much like the television programming game from the December 2011 exam), these games were much more manageable than the final game.

•The other unifying feature of these games? Scenarios. If you determined that each of these games could only play out in a few different ways, and you made some pre-question deductions about what would happen in each possible iteration of the game, all four games on this section could be finished expediently. This isn’t a unique feature of this game set. For whatever reason, almost every game on recent exams is easier with a good set of scenarios. By my count, only one out of the last thirty-six published games was easier without scenarios. So, like, no doy, if you’re preparing for any upcoming exam, spend a significant chuck of your study time figuring out when and how to make these scenarios.

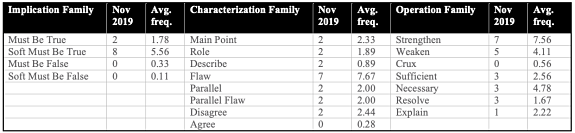

• Nothing in the two scored Logical Reasoning sections struck me as difficult as that final game. Although every LR section has at least a few questions that will leave you gobsmacked, these sections were, on balance, very fair. Here’s how the 51 questions got divvied up …

(The “Avg. freq.” refers to how many of these questions appeared, on average, on each published LSAT from June 2017 to November 2019)

Not too far off from our predictions, but we did dramatically underestimate how many Soft Must Be True questions there would be. Eight Soft Must Be True questions is the most since the June 2017 test, in fact. The prominence of that question type has been trending down in the last couple years, but perhaps the test writers were banking a ton of them to spring upon unsuspecting November test takers.

Principle questions also made a big showing on this exam, with two Soft Must Be True Principle questions and three Strengthen Principle questions. Principles have become increasingly prevalent on recent exams, so make sure you know how to identify and tackle Soft Must Be True and Strengthen Principle questions, since the right approach makes these among the more predictable and anticipatable questions.

• Speaking of other recurrent themes on these LR sections, causation was a huge factor on this test. I counted ten separate questions that involved cause and effect. We should greet the appearance of cause-and-effect relationships with open arms in LR. When the author concludes that a cause-and-effect relationship exists, it’s nearly always a flawed conclusion. When we’re asked to strengthen or weaken a cause-and-effect relationship, there are only a few ways an answer choices might do either. Identifying causation makes these LR questions significantly more manageable, so LR sections that feature this much causation shouldn’t be too tricky.

But what made some of these questions a little challenging was the fact that the test writers seemed to go out of their way to hide the cause and effect. Rather than use classic cause-and-effect words like “results in” or “due to,” they hid the causation with more subtle language like “attract” or “attributable to.” To make sure you’re catching these hidden cause-and-effect relationships, you should always ask yourself if an argument is asserting that one thing is producing a change. Such assertions will always present cause-and-effect relationships — the first thing is causing that change. There are myriad ways to show that one thing is changing something else without resorting to obviously causal words like “causes” or “leads to,” so focus less on the language (although strong, active verbs like “increases,” “promotes,” “reduces,” etc. can be great clues that there’s an asserted cause-and-effect relationship) and more on whether the argument claims that one thing is an agent of change.

• Conditional reasoning, by contrast, was underemphasized on this exam — with only eight questions involving conditional statements or quantifiers. The questions that did feature these concepts, were relatively straightforward, fortunately.

• No one goes to the LSAT for entertainment, but the test writers can usually be counted on for at least one truly dada LR question. I didn’t find any here, unless you found one question’s reference to an “all-cheeseburger diet” whimsical. The test writers were apparently binging HBO programs from this last year, however, with questions referencing both dire wolves and Chernobyl.

• I thought the hardest LR question was a Strengthen question that came late in the second LR section of the released exam. In that question, researchers surmised that the consumption of turmeric in curry helped stave off the cognitive decline of some people in Singapore (this, by the way, was the second question in as many years to discuss the cognitive benefits of turmeric, with a question about turmeric’s ability to prevent Alzheimer’s appearing in December 2017). Apparently the elderly of Singapore who consume curry received much higher scores on cognitive tests than those Singaporeans who did not mess with curry. The researchers then claimed that this relationship was “the strongest for the elderly Singapore residents of Indian ethnicity.”

• An out-of-nowhere reference to people of Indian descent in a question about curry felt, at least to this non-Indian dude, extremely problematic. But if that potentially racist part of the question struck you the same way, it at least pointed us to the right answer. Answering Strengthen questions is always easier if you understand why the argument presented is flawed; the right answer will typically fix that problem. This particular question was difficult because it was flawed in about eighteen different ways. But focusing on that reference to Indian-Singaporeans would have directed us to a major flaw — even if the turmeric in curry does cause people to retain their cognitive faculty into their dotage, why would this relationship be more pronounced for Indian people? The right answer presented a reason why — the curries that Indian-Singaporeans consume have more turmeric than other curries, so the fact that the Indian-Singaporeans are able to stay even sharper in their twilight years reinforces the claim that turmeric can keep elderly people sharp.(Now, the right answer just said “Indian curries” have more turmeric, requiring us to make perhaps another problematic assumption that Indian-Singaporeans who consume curries consume mostly Indian curries … but I’ll leave any further discussions of the LSAT’s cultural sensitivity to y’all.)

• Although Reading Comprehension has been only getting more brutal in recent years, I thought most passages were tolerable here. In the first passage, the author had a major bone to pick to the dull, ahistorical presentation of early-twentieth-century nonfiction films at film festivals. Many noted how over-written the last sentence of this passage was (“It ill behooves us alleged early film lovers to forsake their insights today.”). But so long as you were not left bewildered or bedeviled by the phrase “ill behooved,” the questions were all pretty straightforward. Most were about the author’s claim that we shouldn’t simply display the same kind of films together simply because they’re similar, but we should instead take lessons from how people in the early twentieth century would have programmed those films.

The second passage — the inevitable law passage — should have sounded very familiar to test takers. Much like the legal passage in the September 2019 exam, this one was about how international legal norms and guidelines will have to reckon with climate change. In the November passage, the author complained that the international guidelines that help nations form treaties regarding waterways that pass through multiple countries are inadequate because they don’t consider how climate change will affect those waterways. The questions focused almost exclusively on two claims from the passage: that the guidelines were intended to reflect norms already established by international courts and practices, and that apportionment of water to different countries based on proportional shares might be more fair and flexible than what the guidelines currently prescribe. If you caught these two ideas, the passage would have been … ahem … smooth sailing.

We discussed the third passage — what many alleged to be the hardest passage in the section, about the use of peptides to make microchips smaller — last Thursday. Reading this one again, I was struck by how many extraneous details were in the passage. Most questions in this passage did not require a deep understanding of every last detail mentioned in the passage. As we discussed in this blog post, that’s not uncommon for science passages. They’ll inundate you with details, but focus on the big picture. Usually that’s enough to answer the questions. And if they happen to ask you about a very small detail, you can always go back to the passage to get that answer.

The final passage, the comparative one, fortunately had only five questions. Both passages referred to the Whorfian hypothesis (which, coincidentally but helpfully, was a plot point in the movie Arrival) that one’s native language constrains their thoughts, and both authors looked at that hypothesis somewhat skeptically. The questions could have been much more difficult than they were, but most focused on the general relationship between the two passages.

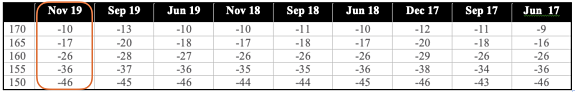

• Finally, let’s discuss the curve of this exam again …

(Each number refers to number of questions you can answer incorrectly and still earn the respective score)

I can’t argue with the numbers the psychometricians who scaled this exam relied on, but this felt like a pretty stingy curve to me. When the hardest part of a test is a logic game, we can usually count on an at least -12 curve for a 170. For instance, we got a -13 curve in September 2019, when everyone thought the hardest part of the exam was the “flower game.” Obviously, not everyone who took this November exam shared my opinion that the fourth game was the hardest part of the test. But I was genuinely surprised to look at this curve after doing that fourth game — I thought that game was a bit more difficult than the “flower game” from September, so I expected a fairly generous curve to score a 165 or 170.

The curve rounded out to be more forgiving for those scoring in the 160 and below. But this would have been a particularly annoying test to those scoring in the 160s who were hoping to crack into the 170s. If that describes you (and if you made it through all 2300 words of this blog, I’m guessing you’re pretty dedicated to earning that high score), I would definitely recommend taking the LSAT again. If you didn’t hit your target score this time, another exam with a slightly more generously curved exam (or a slightly less difficult final game) might allow you to hit it next time.

Search the Blog

Free LSAT Practice Account

Sign up for a free Blueprint LSAT account and get access to a free trial of the Self-Paced Course and a free practice LSAT with a detailed score report, mind-blowing analytics, and explanatory videos.

Learn More

Popular Posts

-

logic games Game Over: LSAC Says Farewell to Logic Games

-

General LSAT Advice How to Get a 180 on the LSAT

-

Entertainment Revisiting Elle's LSAT Journey from Legally Blonde