A Look at the September 2019 LSAT

- by

- Oct 18, 2019

- LSAT

- Reviewed by: Matt Riley

The scores for the September 2019 LSAT were released this Monday, a cause for celebration and consternation for those who took that test. But, for disclosed tests like September, score-release day is also test-release day. On these days, LSAC releases this exam to the public. Us LSAT instructors can marvel at a shiny new object, revel in the new games and passages as we journey through the exam, and attempt to identify trends that can help us discern what future exams may behold.

We’ve just journeyed backwards and forwards through the September 2019 exam, and we’ve just come out the other side with hard-won knowledge and a newfound fear of flowers (seriously, we’ll get to that flower game soon). And, as is our wont, we’ll now accompany you through another journey through this exam. But beware: these posts are always a long and windy road, a veritable field trip through the questions that confronted September test takers. So grab your sack lunch, get your parent or legal guardian to sign the permission slip, and jump into this poorly chaperoned school bus as we put the … ahem … petal to metal and drive through the September 2019 exam.

Logic Games

• We usually start these field trips with Logical Reasoning (we abide by bird rules at Most Strongly Supported — the largest bird section gets first spot in the pecking order), but the talk of this test was the Logic Games section. Boy, did people ever hate the living guts out of this LG section. We were pretty eager to take a look at this section, given the opprobrium thrown its way. So how did it stack up to supposed infamy?

It was definitely a hard section. That much we cannot deny. However, none of the individual games can bang with some of the hardest games of recent exams. Nothing here really touched game four of the July 2019 test, or of the December 2017 test — to say nothing of the curveballs thrown on some of the 2014-16 exams. Heck, there wasn’t even a rule substitution question in this section, which would be a rare treat on a more typical games section. Two things made this games section a little troublesome, though: (1) there wasn’t an outright easy game — the one that warms up your analytical reasoning muscles (wherever those may be located) and builds your confidence for the rest of the section; and (2) the order of the games was a bit unusual — which I imagine compounded test takers’ frustrations.

• The first game was probably the second hardest of the section, which is very unusual. The first game is typically the aforementioned calisthenics- and confidence-boosting one. This game was one of two combo games on this exam (tough break for our in-house prognosticator, by the way, who predicted there wouldn’t be any combo games on this test). We had to select five of eight kittens and puppies– given legitimately aww-inspiring names (seriously, I didn’t know the test writers had this level of charm in them) like Jaguar and Scamp and Wags — to display at a rescue shelter’s adoption event. So that’s the grouping element. But there would be five sequentially numbered pens, one through five, in which we’d place the five chosen pets. So that’s the ordering. Plus, since we were dealing with both kittens and puppies, however, we had to also create a tier of slots in our set-up, which was a lot.

Many test takers complained about this game being super time-consuming. I imagine many of those people rushed headlong, like a puppy to a postal carrier, into the questions. It did take me a long minute to determine the best way to construct scenarios in this game — I ended up making a set of scenarios based on whether two very constrained puppies were selected or not. But these scenarios made the questions super easy. That said, the novelty of the game, the complexity of the set-up, and the hidden cruelty in the tableau (seriously, why not take all the animals to find their forever home at the adoption event?), made this an inauspicious start.

• Next up was a rare “circle” game. And, goodness, do test takers lose their marbles at the sight of a “circle” game. It happened in July of 2018. And it happened again in September of 2019. If you, dear reader, were alarmed by the sight of this circle game, or if you are trembling at the thought of receiving a circle game on a later exam, I have an insider secret to reveal. Lean in close to your monitor, so you can see the next italicized paragraph as clearly as possible. Read over it a few a times if you need to. Absorb it into the very fiber of your being …

Literally no one is forcing you to make your set-up resemble a circle on a “circle” game.

Seriously, just set up so-called “circle” games like a normal 1-to-1 ordering game. Now, you do have to remember that the last slot is “next to” the first slot. Maybe draw an arrow from the last slot to the first one. But the biggest barrier of entry to these circle games is just the novelty of the set-up. So why not just use a set-up you’re familiar with?

Once you have a basic, familiar set-up, you’d realize that this was a fairly straightforward ordering game. There was a block, which apparently could only go in five places. Once you made a set of five scenarios with that block, you’d realize the block could actually only go in three places. You’d answer the questions quickly with your scenarios. Unlike your fellow test takers, your mind would not be spinning in circles.

• As I mentioned earlier, I heard a lot about the so-called “flower game,” which came third. Literally every test taker I spoke to — and most test takers who regaled their experiences online — mentioned this game. Usually with a twinge of trauma in their voice. So I was super excited to check this game out. Based on descriptions, it seemed like it a game without precedent. A sui generis creation. Something that perhaps an LSAT instructor could, from afar, admire as a beautiful and unique creation, but for the test takers who had to grapple with it, a thorny, tear-producing thing — um, not unlike a flower. As a fan of flowers both real and metaphoric, I was pretty excited to check this game out.

This game, however, wasn’t quite the unique creation many claimed it to be. It was, a few twists aside, a fairly standard underbooked stable grouping game. A game in which you’re given a certain number of groups, each with a defined size. In this case, we had five people making flower arrangements, with each arrangement containing exactly four flowers. But, since the game only provided us with four different kinds flowers to use, this game was severely underbooked — certain flowers would recur not only in different people’s arrangements, but sometimes an individual would use a flower more than once in their arrangement. Such games have been a staple of recent exams, having appeared on the June 2019, June 2018, June 2017 and December 2015 exams. They’ve been so prominent that even our frequently wrong predictor was able to accurately predict that the third game would be an underbooked stable grouping on this exam.

There were a few things that were weird with this game, though. For one, the fact that there were five people and four flowers may have led some test takers to believe that the flowers were the groups and the people the players (usually the more numerous variable set should function as “the players” and the less numerous the “groups” in your set-up). But, since we knew how exactly how many flowers would be contained in each person’s arrangement, that variable set had to be the groups. Additionally, the fact that some flowers could go more than once in an individual group is pretty unique on these types of games. Finally, a rule that required each person to have three different types of flowers in their set-up was an added complexity that did, truly, make this game more difficult.

But this game shared some similarities with many recent games — such as the first game of the November 2018 LSAT, the fourth game on the June 2018 LSAT, the first game of the December 2017 LSAT, and the fourth game of the June 2017 LSAT — in that you had to make methodical, restriction-based deductions from the rules. The limited number of flowers to choose from meant that once you were able to determine that one or two types of flowers couldn’t go in a person’s arrangement, you’d have a pretty good idea of what that arrangement looked like. And mostly these deductions came from knowing what the words “exactly” and “at least” mean. And like almost every recent game, there was a rule that created a couple of super solid scenarios.

If this game wrecked your September test day and has induced flora-based nightmares since, please don’t take all this the wrong way — this was still a quite difficult game! And of course, it’s much easier for someone to figure a game out in a comfortable and untimed environment than it would be during the mad dash of test day. But — and this was also true of the preceding “circle” game — games like these are always easier if you assume you’ve done something like it before (you probably have) and use a set-up you’re familiar with. Assuming the contrary — that the game is completely novel, without precedent — tends to lead test takers into an unnecessary spiral.

• Like an aged rock band on a reunion tour, the September LSAT closed things out with a classic — a scheduling combo game. We had three days of the week — Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday (and I would not be the first to note that this would be abbreviated to “WTF” in your set-up) — and a morning slot and afternoon slot on each day. This game was fairly straightforward rendition of an LSAT standard — there was a very constrained player whose placement led to four very helpful scenarios — not the sort of over-the-top craziness the “WTF” promised.

• So what can we take away from this games section? Well, once again, this section continued the trend of scenarios being helpful on every game. This has been true, in my opinion, on almost every recent exam. And on the recent sections in which this hasn’t been true, scenarios have been helpful on only three of the four games. So, not to state the obvious, you should be studying up on how to make scenarios, practice making them during your studies, and then actually construct them on test day.

But this exam also illustrates how important it is to trust your experience on these games. If you study extensively — and anyone reading this treatise on the September exam is presumably studying quite extensively — you’ll have almost certainly seen some variation of every game you confront on your exam. Test takers err when they panic — when they assume that the game is completely unfamiliar. But remember, these entirely unique games on the LSAT are few and far between. Honestly, in this millennium, I think there has been precisely one truly unique game (the computer virus game from the September 2016 exam). Everything else has at least some precedent. So try to approach each game using the set-ups, tools, and experience gained from older games. Even if a game seems unique — as the circle and flower games may have here — it’s important to interrogate it, to see if there’s a way to make it familiar. There pretty much always is.

Logical Reasoning

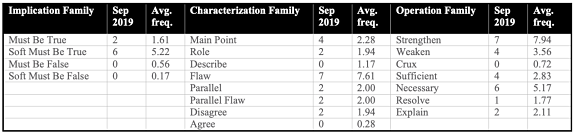

• Onto Logical Reasoning. Here’s how many of the different question types appeared across both LR sections, compared to the average number of appearances per test since the December 2013 test:

• As you can see, this was a pretty balanced set of questions included. No single question type dramatically exceeded or fell short of its average frequency. That’s pretty normal on a September test, by the way. For whatever reason, September exams have — for want of a better word — a pretty “normal”-feeling Logical Reasoning section.

• If there was anything peculiar about these Logical Reasoning sections, it was the distribution of the difficult questions. Like the narrative thrust of the classic three-act drama, the difficulty of a Logical Reasoning section typically starts slow, gradually rises, climaxes, then recedes in a dénouement in the final few questions. Both of these sections started with some mild questions, and coasted on that setting throughout the entire section, until question twenty-one or so. And then there was a gauntlet of brutally difficult questions.

• Two very difficult sections stuck out to me: questions twenty-four and twenty-five in the LR section with 26 questions. Question twenty-three was a Weaken question that argued that experiencing a traumatic event might stimulate the production of cortisol — a steroid hormone produced by the pituitary gland, but that’s not important. To support that claim, the argument showed that people who experienced a traumatic event but did not develop PTSD have higher cortisol levels than those who have not experienced a traumatic event.

So classic correlation to causation issue, right? On a typical Weaken question, the correct answer would weaken such a causal claim with an alternate cause (something else that may trigger the cortisol production in those non-PTSD-afflicted individuals), showing the cause frequently appears without the effect (perhaps by showing that people who experienced a traumatic event who did develop PTSD did not have higher cortisol levels), or showing the effect frequently appears without the cause (perhaps by showing that, contrary to what the stimulus said, people who have not experienced a traumatic event frequently have high cortisol levels). This, being an atypically difficult Weaken question, did not feature any of those in the answer choices.

The right answer presented what could be considered an alternate cause or cause without the effect only if you looked really, really closely at it. That answer choice claimed that the high cortisol levels in the people who did not experience PTSD helped those folks not develop PTSD. So it wasn’t the traumatic event that produced the high cortisol levels — it was a defense mechanism that produced the cortisol (which would be an alternate cause). Or, we could say that the answer choice introduces the possibility that those people who experienced a traumatic event and did develop PTSD do not have high cortisol levels (which would be the cause appearing without the effect).

But this question would probably have been easier to understand if we understood that it was also committing a sampling fallacy. In order to establish that traumatic event increases cortisol levels, we’d have to compare a representative sample of everyone who has experienced a traumatic event to a representative sample of everyone who didn’t. By only including people who didn’t develop PTSD, we were looking at an unrepresentative sample of those who experienced a traumatic event. The correct answer, then, shows just how problematic it is to only rely at the people who didn’t develop PTSD — they probably had abnormal levels of cortisol, compared to those who developed PTSD, if the cortisol helped them stave off PTSD.

The take-away from this question? It’s important to remember (memory, incidentally, is aided by cortisol) that sometimes difficult questions commit more than one fallacy. Focusing too closely on just one may make it difficult to find the correct answer. It doesn’t hurt, then, to try to take inventory of several fallacies that may be committed on a difficult Flaw, Parallel Flaw, Strengthen, Weaken, or Necessary question that appears towards the end of a section. Doing so might make these questions less of a traumatic experience.

• In a cruel twist, the very next question was another super difficult one. Question twenty-five was a Must Be True question that involved proportional reasoning. OK, imagine I told you I ordered a pizza, all to myself, both yesterday and today (if you know me, this shouldn’t be difficult to imagine). But let’s say today I ate a way higher percentage of my pizza than I did today. Let’s say I ate half of the pie yesterday, but I ate all of the pie today. But what if I also told you I ate same amount of pizza, by weight, today and yesterday. So I ate a greater percentage of the pizza today, despite the same amount of pizza today. What could you conclude about the relative sizes of the pies I ordered, yesterday versus today? Well, it must be the case that I ordered a smaller pizza today (today’s pie would technically be half the size of yesterday’s), if I ate the same amount of pizza but got through more of the entire pie.

OK, now replace “eating pizza” with “commercial fishing in all the world’s oceans” and “sizes of the pies” with “the total number of fish in all the world’s oceans,” and you have question twenty-five. That question told us that after 1995, commercial fishers were catching the a greater percentage of the fish in the world’s oceans year after year. But also, after 1995 they were were catching the same (or a smaller) amount of fish, by weight, year after year. From that, we could conclude that the total population of the world’s fish was declining, year after year.

If you understand the basics of proportional reasoning, you’d be able to get this question. But this type of reasoning is rarely invoked on the LSAT (and when it is, it’s usually in the context of flawed arguments), so it probably stumped more than a few test takers. In the rare event that this type of reasoning recurs on a later LSAT, here’s all you need to know. And since I am definitively not a math person, I can only convey this info through a pizza analogy.

Three elements define this type of reasoning: percentages (this would be how much of the pizza pie you ate), amounts (this would be how much pizza you ate, by weight), and the total size (how large the entire pizza is). When you have information on two of these elements, you can usually make a valid deduction about the third. So if I told you that today I ate a smaller percentage of the pizza pie I ordered, but I ate the same amount of pizza both yesterday and today, you’d be able to conclude that today’s pizza was larger. Or if I told you that today I ate more pizza than I ate yesterday, but the pizzas were the same size both yesterday and today, you’d be able to conclude that I ate a higher percentage of the pizza today. These questions will in all likelihood not involve pizza, but the logic remains the same.

• These, and a few other questions aside, neither of these Logical Reasoning sections were all that challenging. It’s unsurprising that most test takers’ ire was reserved for Logic Games and not to LR or Reading Comp.

Reading Comprehension

• In what was a welcome respite from recent exams, this Reading Comprehension section wasn’t as distressingly difficult as recent sections. Apparently, it’s not just pop music that’s feeling nostalgic for the early 2000s — this section was a throwback to that era’s milder Reading Comp sections.

• The first passage argued that Great Zimbabwe — a flourishing, enclosed city-state from the ninth through sixteenth centuries (think Qarth from Game of Thrones) — owed its prosperity not to gold, as previously thought, but to cattle raising. The questions were detail-heavy, but — unlike the large-scale efforts the ruling class of Great Zimbabwe to harness cattle and mine gold — not particularly demanding.

• Passage number two was the comparative passage; passage A argued that historical fiction requires the telling of effective lies (such as modernizing language, and inventing characters and dialogue), while passage B argued that autobiographical fiction is sometimes enhanced by false, but vivid and emotionally resonant, memories. These passages had a more direct and discernible relationship than most recent comparative passages, and the questions were accordingly a tad easier than most recent comparative passages.

• The third passage was the inevitable science passage. It involved a sort of terrifying discussion on how a microbiologist discovered that cholera could exist in a dormant state in sea water, contrary to the previous belief that it could only be spread by human hosts, and that cholera was consequently much more prevalent than previously believed. The questions featured a “resolve” question — fairly common in Logical Reasoning, but super rare on Reading Comp. Even with this rare question type, this passage was a tad less challenging than many science-based passages. Less stomach-churning than a cholera infection, at least.

• The final passage was the inevitable law passage, on international environmental law. This somewhat hectoring passage argued that nations don’t quite practice what they preach, given that most nations profess to accept the norm that they do no harm to other nations’ environments, but do all sorts of things that spread pollution to other nations. The author argues that scholars of international environmental law should reckon with this fact. This was probably the most challenging passage, but each of the correct answers were well-supported by the passage.

The “Curve”

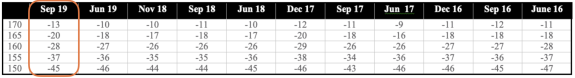

• Here’s a chart listing how many questions you could have missed on the September 2019 exam and still earn a given score, compared to the same figure for other recent exams:

• You, frankly, love to see it. As we discussed before, we were expecting a generous curve on this exam. And, at least for the higher scores, we were correct.

It’s been a while since we’ve had a -13 curve for a 170 score — June 2014, in fact. And we haven’t had a -20 curve for 160 since December 2017. A forgiving curve for those high scores means that test takers who score in that range had a harder-than-usual time with difficult questions, passages, and games. With some of the invectives test takers threw at that flower game, we didn’t exactly need the curve to confirm that fact.

You’ll notice, however, the curve starts normalizing once you start looking at the 155 and 150 scores. Given that there were many mild Logical Reasoning questions and a relatively moderate Reading Comp section on this exam, this also makes sense — your “average” test taker scoring in the low- to mid-150s would have had a fairly normal time with those questions.

What to Expect Moving Forward

And thus ends our long field trip through the September exam. And, as in the field trips of our youths, we have to kind of wrap things up with a “what did I learn” essay. So, what did this LSAT teach us about what future LSATs, like the upcoming October and November LSATs?

Maybe not a whole lot? This LSAT is fairly anomalous in terms of the distribution of difficult questions. Most recent LSATs have featured much more difficult Reading Comprehension section than this one. And most have featured a greater number tough and brutal Logical Reasoning questions, rather than the few brutal questions this exam featured. And there hasn’t been a Logic Games section this novel, or this difficult, since the September and December 2016 exams.

So if for whatever reason this was an especially difficult test for you — and if you’re planning on taking the upcoming October or November LSATs — I wouldn’t expect to see an LSAT that looks exactly like this. Keep studying Reading Comp, because in all likelihood those exams will feature a tough RC section. Practice a broad range of Logical Reasoning questions, because those exams will likely feature more tough and brutal LR questions than this one. That said, it never hurts to be over-prepared — so if you want to tangle with some incredibly difficult games on the off-chance those exams might feature some brutal games as well, we encourage you to do so.

Search the Blog

Free LSAT Practice Account

Sign up for a free Blueprint LSAT account and get access to a free trial of the Self-Paced Course and a free practice LSAT with a detailed score report, mind-blowing analytics, and explanatory videos.

Learn More

Popular Posts

-

logic games Game Over: LSAC Says Farewell to Logic Games

-

General LSAT Advice How to Get a 180 on the LSAT

-

Entertainment Revisiting Elle's LSAT Journey from Legally Blonde