Unlocking Logic Games with Organization

- by

- May 25, 2017

- LSAT

- Reviewed by: Matt Riley

Note: As of August 2024, the LSAT will no longer have a Logic Games Section. The June 2024 exam will be the final LSAT with Logic Games. Learn more about the change here.

The more I work with LSAT students, the more I believe that the way you organize your work on the Logic Games affects your overall performance. I’ve seen a lot of students who are struggling to understand games or find deductions, and often when I look at their homework, it’s hard to even figure out what they’re doing because their work is all over the place and totally disorganized.

This is, of course, bad. Despite what you may think, the way that you organize your work for Logic Games makes a big difference on your performance, and the best practice is not to use up as much of the white space on the page as you can. Instead, your work should be kept to a limited, but well-organized, area. This is for two reasons: 1) speed, and 2) ease of finding deductions.

1. Getting faster (without getting furioser)

In the past, LSAT Logic Games were always on a single page. Although it required writing a lot smaller (and it was sometimes tough to squeeze your work onto that single page), I actually believe that the old format was faster because you weren’t looking back and forth between pages so much. The farther your eye has to travel to see your master diagram or check the rules, the longer the game is going to take you, and the more likely you are to forget crucial details as you look back and forth.

Now that the games are split across two pages, the questions are always going to be more spread out, but that doesn’t mean that your work should be spread out. I recommend writing your master diagram on the second page, close to the questions. Then, as you create smaller mini-diagrams for each question, those should be next to the relevant question (or as close as possible). That way, you’re never doing too much back-and-forth scanning.

2. Deductions become … elementary, my dear Watson

Deductions are found by looking at all of the different rules, and seeing how they interact with each other. For instance, if one player appears in multiple rules, that often leads to a deduction. When I am doing a game on my own, I always start the process of finding deductions by going through each rule, one by one, and examining how that rule fits with the other rules and with the general set-up.

As I tutor students, sometimes I’ve found that they try to squeeze their representations of the rules next to the actual text outlining the rule. Students also frequently write rules willy-nilly all over the page, or don’t clearly show the contrapositive to conditional rules, and so on.

It’s much harder to compare the rules (and, therefore, find the deductions) if you can’t understand your work just by glancing at it. Therefore, you should keep all your rules in one spot, and write them as neatly as possible.

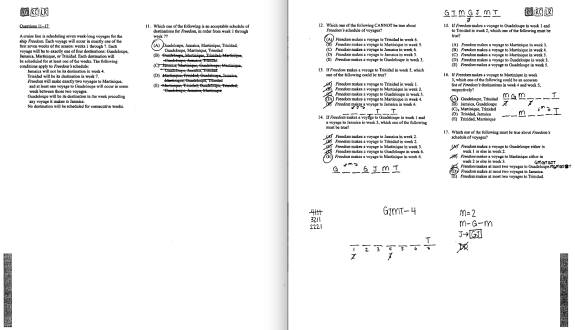

With these ends in mind, here’s a mock-up of an actual logic game from the June 2007 LSAT, with my actual set-up and work.

Here are a few things to notice:

1. For the first question, the Elimination question (where you check rule-by-rule to find answer choices that violate each rule, and knock the offenders out), I’m crossing out all of the text of each answer choice. That makes it easier to skim the remaining answer choices for the subsequent rules.

2. My main set-up is kept in a limited part of the page, with each rule clearly represented in a line and in one area. That makes it easier to find deductions, because I can quickly and efficiently cross-reference the rules.

3. For each question, I drew my smaller hypothetical as close to the answer choices as possible. That made it easy to check against the diagram as I looked at each answer choice.

Part of your review process for each game should be figuring out whether your performance was hindered by the way you arranged the main diagram or the smaller hypothetical diagrams. If you find that your set-up does more harm than good, then you’ll need to tweak your approach for the next one.

Search the Blog

Free LSAT Practice Account

Sign up for a free Blueprint LSAT account and get access to a free trial of the Self-Paced Course and a free practice LSAT with a detailed score report, mind-blowing analytics, and explanatory videos.

Learn More

Popular Posts

-

logic games Game Over: LSAC Says Farewell to Logic Games

-

General LSAT Advice How to Get a 180 on the LSAT

-

Entertainment Revisiting Elle's LSAT Journey from Legally Blonde