Let’s just hope that we don’t have eight people only voting for president.

The 2000 Presidential Election—where Bush beat Gore, taking 271 Electoral College Votes to Gore’s 266, but losing the popular vote by about 500,000 votes (at least officially) —brought us Bush v. Gore.

An automatic machine recount revealed that the margin of victory in Florida was only 327 votes in favor of Bush. In the American winner-takes-all electoral system, this meant that Bush would take all of Florida’s 25 electoral votes and with them the presidency.

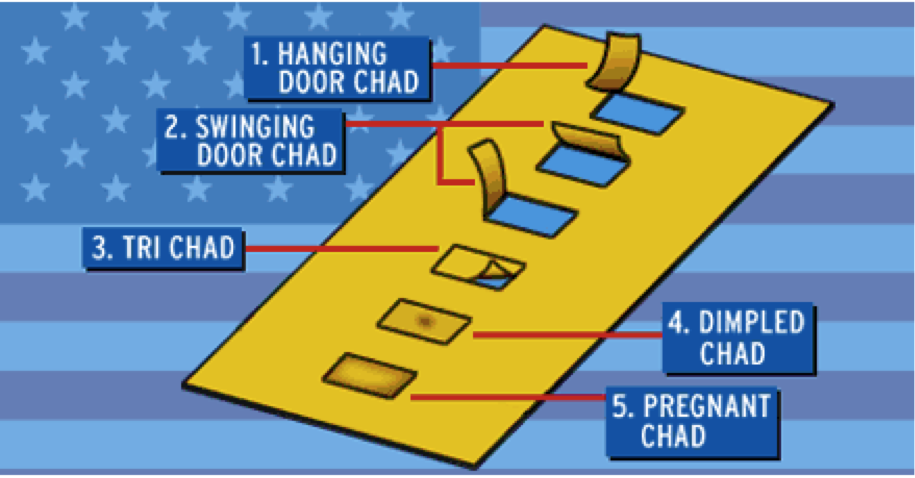

So Al Gore decided to sue to force Florida to do a hand recount. He wanted votes in four predominantly Democratic counties recounted. One of the problems with the Florida count was that Florida employed punch-card voting machines—essentially a technology from the 1960s. Voters would have to use a little dowel to punch a hole in a card next to the name of the candidate they wanted to vote for. But often the cards wouldn’t get punched all the way through. The little piece of paper a voter was supposed to poke out, called a “chad,” would sometimes stay attached to the card and would therefore cause the vote-counting machine to misread the card. There were even different colorful terms to describe the different degrees to which the chads clung to their respective holes.

Gore got his wish from the Florida Supreme Court, and a recount ensued. But the U.S. Supreme Court, on appeal from Bush, put a stop to the recount. The reason the Supreme Court stopped the recount was because each county in Florida made up its own standards for how to run the recount. Bush successfully argued that this variation in standards between counties—such that in one county the same exact card would count whereas in another it wouldn’t—violated the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment. Seven out of nine justices of the Supreme Court agreed with Bush.

However, the second part of the Supreme Court decision was more contentious. The Supreme Court, voting along party lines, decided 5 to 4 that a recount could not continue, and indeed would not happen at all, because there was not enough time to implement a uniform standard in time to meet a statutory deadline for appointing electors. That deadline was December 12th, the same day the opinion was issued and just a single day after oral argument.

Bush v. Gore is sometimes held out as an example of the justices putting their partisan goals over the Court’s need to appear legitimate and therefore impartial in the eyes of the public. The Supreme Court is supposed to be above politics, and in deciding a presidential election it appeared to be very political.

The actual details surrounding the case paint a more complicated picture. Sure, on the key issue—whether the recount could continue—, the justices voted their party affiliations. But the issue with the deadline, and the fact that the threshold issue—violation of the Equal Protection clause of the 14th—went 7 to 2 for Bush, make Bush v. Gore a bit more complicated.

The circumstances around Bush v. Gore taught us that every vote really does count . . . well, at least in Florida, and at least if the Supreme Court lets us count it. An independent study commissioned by several news organizations revealed that under any uniform recount, Gore would have won by about 100 votes.

Let’s hope we won’t see a Trump v Clinton.