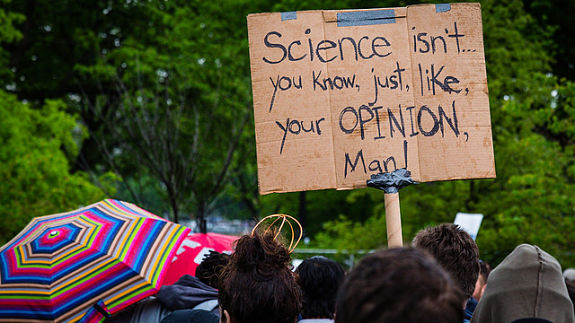

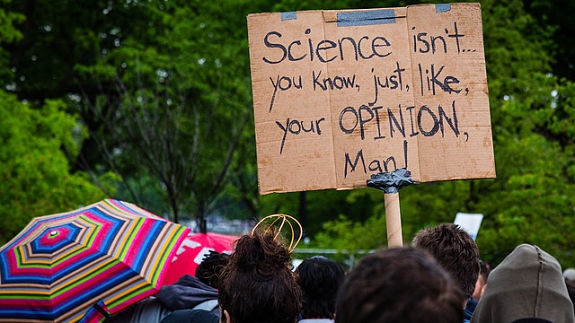

We may be living in a “post-truth” society, but the truth made a strong comeback this weekend. Thousands of protesters marched Washington, D.C., and hundreds of other cities, to defend truth and facts. Specifically, the scientific method for discovering the truth, which protesters argue is under attack from a culture and—though the protests were billed as non-partisan, let’s face it—a presidential administration that value opinion and partisanship over facts and empirical evidence.

To those of us that value logic and empiricism and sound methodology, these protests were inspiring. And, through protest sign after protest sign of science-themed puns, clever.

Some, who may lack a B.S. but plan to use a liberal arts education to get into law school, may want to use this experience in these marches as a personal anecdote for the personal statement in their law school applications. “I want to become an attorney to pursue the truth, an ally to those I marched with on April 22, 2017.” Some even may want to connect this experience with the tireless pro bono lawyers who represented those detained following the travel ban back in January. “I also am inspired by those attorneys who upheld justice by dedicating their time to representing those separated from the families by the travel ban.” The pursuit of truth and justice as a career—it does have a very promising ring to it

These are incredibly noble aims, and I would certainly encourage you to pursue these ends if they are your passion. But, if you are thinking about using this weekend’s marches as a topic for your personal statement, or in an admissions interview with an alum, or just bringing it up with your lawyer friends, it may be helpful to go over how the law’s pursuit of the truth is different from science’s.

Science, in a rare instance of smart branding, named a whole process of truth-seeking after itself. The so-called scientific method involves observing phenomena, developing hypotheses about that phenomenon, and testing those hypotheses with experiments, data acquisition, and further observation. Any conclusions made will be tested and retested, and hypotheses are refined and altered until a collective understanding of how the world works is achieved. And that collective understanding is what’s called the truth. This is reductive take on a very complex and serious method of inquiry—look, I’m not a scientist, but I did watch a four-minute video about the scientific method that was aimed at children, and I feel like I got the gist of it. But the salient point for our discussion is that science views the pursuit of the truth as an exacting step-by-step process where everyone is more or less working together to reach the truth. It’s a system that attempts to remove bias and self-interest to a huge degree, even requiring extensive peer review of each step along the path to truth.

The law’s pursuit of the truth—in the US, at least—is really, really different from this. The pursuit of truth in law is via the adversarial system. We’ve all watched Law & Order: SVU and know how this system works, but it may bear repeating in this context, to show how weird it is as a truth-seeking process. The adversarial process involves two competing parties—say, a plaintiff and a defendant, or a prosecutor and accused—competing in a courtroom to prove to a neutral third-party—say, a judge or jury—which party’s “truth” shall prevail. The idea is that if both sides are doing their job, pursuing their truth, the actual, objective “truth” will emerge. But we can put “truth” in scare-quotes because, of course, each party is trying to prove the truth that is most advantageous to its interests. These questions of “truth” in law involve really big stakes—maybe not ice-caps-melting-and-drowning-us-all stakes, but huge amounts of money- or depravation of freedom-level stakes, at least. So each side is pushing a version of the truth that is beneficial to its interests. It’s hard to imagine a system of inquiry more reliant on self-interest to make it all work.

To put it another way, if truth is the prize at the bottom of cereal box, then science’s pursuit of truth is the careful and exacting removal of each piece of cereal, to confirm that each piece of cereal is not the prize, while a group of peers review each step of the process to make sure no one is messing up, until the prize is finally found. The legal system’s pursuit of the truth, on the other hand, might be compared to two crazed children ripping the box apart from both ends, until the cereal and prize spill over the floor, allowing a neutral third-party to determine which child the prize landed closest to.

So what is lawyers’ role in seeking the truth? Well, lawyers don’t act as truth-seekers, per se. Lawyers are rather advocates for their clients’ interests. They work to ensure their clients’ interests are represented and advanced within the legal system. They work less towards the truth than towards justice. By representing their clients’ interests above all else, they ensure that they system doesn’t trample over their clients’ rights.

Put next to the objective and rigorous truth-seeking process of science, the adversarial system might seem wanting. But it’s also the system that guarantees that everyone gets a fair (or, more realistically, fair-ish) shake at advancing his or her cause. It allows lawyers to do things like represent defendants they know are guilty or liable (or, in far too many cases, when the wisdom of the masses “knew” they were guilty), to make sure their constitutionally-guaranteed rights of due process and equal protection won’t be denied. It’s also a system that can (and should!) be put to noble ends, whether that’s defending civil rights at home, human rights abroad, the rights of indigent clients, the environment, or really any other cause that requires a tireless advocate.

So when thinking about what your role will be as a truth-seeker, future-lawyer, it’s important to note how those ends will be achieved in the career you have chosen. At the very least, dropping “adversarial system” in a personal statement will make you seem smart and informed.