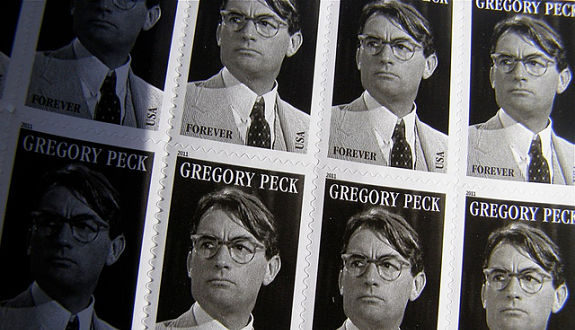

Gregory Peck, all of America wants you to be our dad.

As America bids farewell to its own real-life Atticus Finch, I thought it would be a good time to watch #1 on the ABA’s List of the 25 Greatest Legal Movies, the legendary…

To Kill a Mockingbird

1962 dir. Robert Mulligan

The world is a confusing place for a child. Our moral instruction – to the extent that we get any – is a thicket of contradictions. Even when the right thing to do is clear – and usually it’s not – it’s not always possible. All too often, the good guys toil in obscurity, or are locked away in dark places, while demons are free to run amok.

It’s useful, when growing up in such a world, to have an Atticus Finch around the house to interrogate. Atticus, the hero of “To Kill a Mockingbird” and the Western canon’s archetypal Good Dad, can explain just about anything. And even hard truths sound acceptable when pronounced in Gregory Peck’s deep, soothing timbre.

One hard truth: morality is complicated. Sometimes principles need to be defended. Other times, exceptions need to be made. Lying can be a moral act, and so can having the courage to tell the truth. Nowhere are the lines blurrier than in court, where justice and the rule of law grow together and apart, like vines encircling a trellis. That’s where Atticus plays his other archetypal role: that of the ultimate movie lawyer. He’s brilliant in court: calm, incisive, passionate. More importantly, he’s principled: he knows the system isn’t perfect, but he resists the lure of cynicism and is determined to fight for justice within the parameters of civil and criminal procedure.

As a lawyer movie, “To Kill a Mockingbird” draws on many of the tropes we’ve seen throughout our search for the GLMOAT: the crusading attorney (who takes the case reluctantly), the innocent defendant, the left-handed criminal, and the compromised victim, to name a few. Atticus is assigned to defend Tom Robinson, a black man accused of raping a white woman. Since it’s the rural South, trying the case will come at a tremendous personal cost, but Atticus feels compelled to accept it on principle. As it turns out, Tom is innocent. But with an all-white jury, it’s not clear whether even Atticus can save him.

Outside of the courtroom, “To Kill a Mockingbird” follows Atticus’s two children, Scout and Jem, as they navigate and try to make sense of the world. Re-watching the movie as an adult,, I have to say: the book is way better. While the film is a faithful adaptation, the script’s compression leaves out a lot of the novel’s coming-of-age arc. And so much of the book’s success depends on Scout’s narration. While the film smuggles some of it in in the form of voiceover, it can’t make you see the world through a child’s eyes the way the book does.

So should LSAT students see “To Kill a Mockingbird”? Of course they should! It’s an undisputed classic, an effective piece of filmmaking, and an iconic lawyer movie. But they should read the book first. And then they should study a lot, ace the LSAT, and go make Atticus Finch and Barack Obama proud.