If you think that standardized tests are a new phenomenon, then you think like somebody who is wrong about something. While looking for some good mail order cod, I inadvertently came across the Chinese Imperial Examination System, which is pretty much what it sounds like. That’s right, kids. It turns out that standardized tests have been with us for over a thousand years.

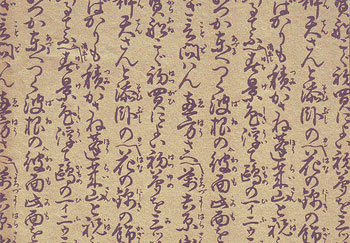

This, the very first standardized test, began in its modern incarnation in the 500s. To put that in perspective, this was the century when Muhammad was busy being born. The exam was used to land sweet, sweet government jobs (a desire that transcends all eras and cultures, apparently). And passing it made you a bona fide badass. If you think the LSAT is bad, the passage rate was between one and five percent. I don’t find this terribly surprising, considering that I wouldn’t stand a chance at either the archery or horsemanship sections. But the exam also tested more standard-issue areas such as writing, math, taxation, calligraphy, and Confucianism. And while you guys might be bemoaning your three-hour nightmare that is the LSAT, these things lasted one to three whole days.

Apparently cheating and bias aren’t modern inventions either, as there were a number of safeguards. For example, test-takers had ID numbers instead of using their names, and someone actually went through the process of rewriting all their tests by hand before going to be graded, so that test takers couldn’t be identified by their handwriting.

And yes, even back then, test-prep accessibility was an issue. It was supposedly a great equalizer, as even a peasant could take the test and rise through the ranks. But it wasn’t always so simple:

“In reality, since the process of studying for the examination tended to be time-consuming and costly (if tutors were hired), most of the candidates came from the numerically small but relatively wealthy land-owning gentry. However, there are vast numbers of examples in Chinese history in which individuals moved from a low social status to political prominence through success in imperial examination.”

If that sounds uncannily familiar, consider this:

“The personal suffering that individuals underwent both in the preparation and in the taking of these exams has become part of Chinese lore. Candidates were known to repeatedly fail exams. Some committed suicide because of the disgrace that these failures brought to their families. Others continued taking exams even as very old, grey-haired men. For those who rose through the ranks by passing these exams and being selected for administrative positions, it meant that their clans or families also rose in social prestige and wealth.”

Things change, things stay the same.