The Alarming Number of October 2010 LSAT Takers

The Alarming Number of October 2010 LSAT Takers

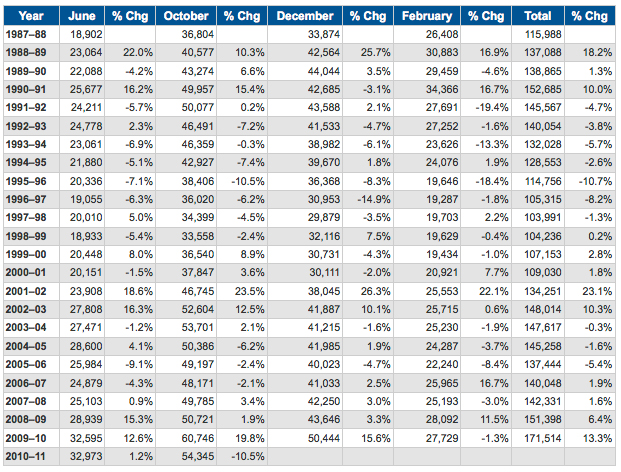

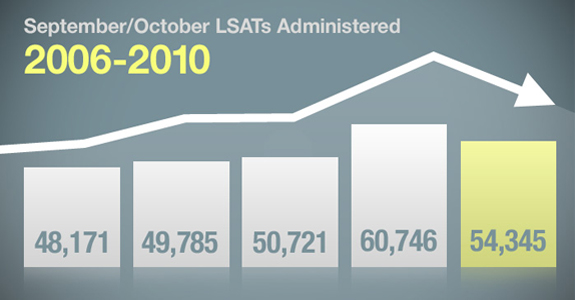

Last year, 60,746 test takers sat for the October LSAT, the single largest administration of the LSAT in the history of the test according to Wendy Margolis, Director of Communications for LSAC. Upon hearing the numbers, the legal profession groaned: dire predictions ensued and warnings to pre-law students were issued. Alas, the collective weight of the profession was not enough to dissuade would-be lawyers and June of 2010 constituted the single largest number of June test takers, ever.

Would the October 2010 LSAT continue the alarming trend? Small picture answer: no. 54,345 test takers took the October 2010 LSAT, a decrease of 10.5% from the previous year, but still the second highest single administration in the history of the test. (For the full chart of the number of LSAT administrations, see below).

Suggesting that the decrease in the number of October test takers indicates that the rush to law school is ending would be like pointing to this summer being cool as a refutation of climate change. Sure, it wasn’t the hottest summer on record, but it was the second. The overall trend is still concerning.

As stories of first year associate delayed job starts, dwindling firm bonuses, and concerns about law school debt abound, one wonders why people continue to line up to attend law school. The whole situation is akin to a paradox question on the LSAT: given that there are fewer law jobs, why does the number of people taking the LSAT and applying to law school continue to increase? Hasn’t enough time passed since the heyday of the legal profession that prospective students should be aware that the luster is gone?

NALP

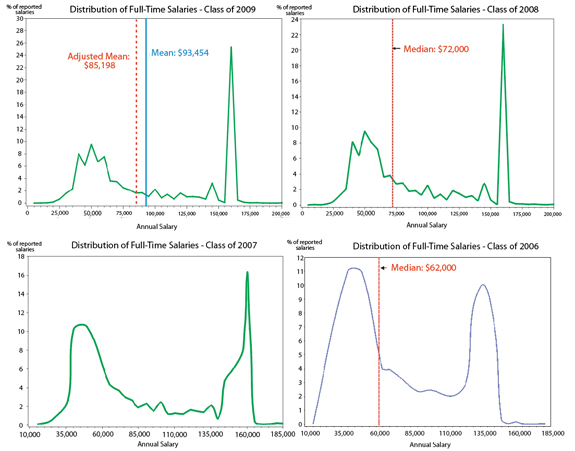

Although part of the cause may be attributed to a lack of knowledge, a far more interesting question revolves around those students who know the state of the legal profession and yet continue to apply. For this population, the beginning of an answer may be found in figures released from The Association for Legal Career Professionals (NALP) in March of this year.

The graphs demonstrate an interesting story. Although the median legal salary between 2006 and 2009 hasn’t changed alarmingly (from $62,000 in 2006 to $85,198 in 2009), the distribution over the same years has become hugely skewed. The legal salaries clustered in the middle—around the $80,000 mark—have been sucked out like a dust pile under a Dyson DC24. Instead of a consistent apportionment, we see a steadily lengthening distribution with spikes clustering around the $50,000 and the $160,000 range.

The phenomenon oddly, or perhaps fittingly, echoes the current economic climate in the U.S in which the top 1% of Americans take home nearly 24% of the income. The middle class—and apparently middle range law jobs— have become casualties of an unhealthy economy.

So what?

These twin peaks would seem to account for the vast disparity between the deep concern on one hand and the hopeful trust on the other regarding the viability of law school as a way to earn a good salary. The legal profession points to jobs at the low end of the spectrum while would-be law students focus on the BigLaw starting salaries of $100+K. Indeed, a Kaplan survey earlier in the year indicated that while 52% of students were “very confident” they would obtain a legal job upon graduation, only 16% were similarly confident in the majority of their peers’ abilities to land a position. It seems that, as long as marquee legal jobs are out there, there are students who feel they can get them, even in the face of extreme statistical unlikeliness.

What should you do if you want to go to law school?

If you’re considering law school, the first thing to do is attempt to calculate the ratio of probable debt to probable earnings. According to Forbes, the average law graduate is $100,000 in debt. To translate this into real terms, 100,000 of debt with 6% interest necessitates $1,400 a month in income just to service the $850 a month it will cost you to pay off the loan in fifteen years. And that’s before you’ve laid out a cent on food, a mortgage, a car payment, or the new waffle weave Henley from L.L. Bean.

Of course, it’s difficult to foretell what your earning potential is likely to be, given the disparity in payment levels even among students from the same school. For instance, I know of two graduates from Southwestern Law School. Both were on law review, but one was employed by an AM-Law top 50 firm upon graduation while the other was hired by a less prestigious firm. The former started at about $160k annually, whereas the other started at about $80k. Ironically, their law firms are in adjacent buildings with the more prestigious firm on the higher floor. The latter literally spends her days looking up at her former classmate.

For a better sense of debt to earning ratio, I would normally tell prospective students to look at the employment rates and salary statistics put forth by the law schools themselves. However, these have come under a great deal of fire lately, with so-called “scam blogs” calling for more transparency in law school reporting.

Better is better

So individual cases aside, it’s probably your best bet to understand the way the system works: typically the better the law school and the better your ranking within your class, the better your chances at landing a premier law job. If BigLaw isn’t your thing, this still applies for obtaining prestigious non-profit and clerking work. Our recommendation if you’re shooting for a prestigious job? Go to a top twenty-law school and perform well once you’re there.

There’s also an important financial consideration, as well. If you have the numbers to get into a top twenty-law school, then you almost certainly have the numbers to obtain substantial financial aid at a lower ranked school. The tradeoff might be a less prestigious job, but you won’t have the debt that necessitates it in the first place.

In order to do either of these things, however, you’re going to need to have a high GPA and, most importantly a high LSAT score, (think 168 – typically the 97thpercentile) or higher. The truth is that while there are still good law jobs to be had, the legal profession is flattening while the amount of people trying to get in is surging. Make sure you know exactly what you’re getting into, and that you really want to be a lawyer. Then, if you ultimately decide to make the leap, make sure you do it with the best LSAT/GPA combination you can achieve.