So they asked me to write something about an LSAT-related topic I’ve been thinking about. So, being friendly-neighborhood-Trent, I complied. Then they asked for another one, and so I popped another one out.

Problem is that I might not have considered the relationship between the content contained therein.

In class, I always have an impossible time trying to convince people that there are many conditional claims they’ve accepted as true, and yet have failed to conjoin. So, I argue, many people will accept ‘A implies B’ and also accept that ‘B implies C’, but because these lie at the periphery of their minds, or because they’re lazy, or whatever, people commonly fail to recognize that they’ve accepted two claims which jointly allow an inference. So these same people might well fail to draw the inference that ‘A implies C.’ No one ever buys this story because they claim that you’d have to be a fool to (a) accept both propositions as being true and (b) fail to recognize their relation to one another. I still think it’s super common, but perhaps that’s because it’s just common for me. And by common I mean it might have just happened to me. As in some readers have thought you could do that with my last two posts. Sucks. But here’s how it lays out….

In my last post, I related the findings of cognitive research into the sources of genius, which was earlier reported in the New York Times. The short version is that genius appears to be the result of hard work, but crucially, hard work that is sustained by intense concentration over long periods. That’s great healthy-nice-person news. So, I urged all readers to go home and concentrate.

The problem is that in the post right before that one, I discussed the growing use of smart drugs in prestigious academic institutions. The short version is that while these drugs don’t give you perfect recall or massively increased analytic ability, they are reported to significantly increase both the extent and depth of one’s concentration.

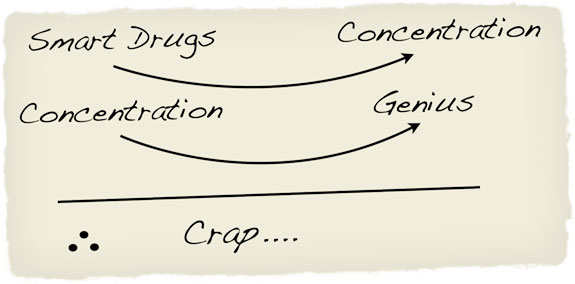

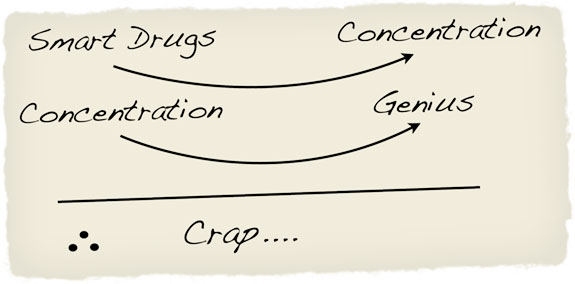

So then I went off to my humdrum existence of suffering and forgot about the whole thing. But readers got to check out these two posts next to one another and came up with the following:

Smart drugs can substantially increase concentration. Increased concentration is obviously necessary for development of genius, but some researchers argue that increased concentration is the key element in the development of genius. This encourages the inference that increased concentration + the stuff you already have (hard work, some innate mental capacity) might be sufficient for genius. Then we get the following scary argument. Smart drugs allow increased concentration, which in turn promotes the development of genius. So smart drugs will make you a genius. Teti even said so…

Ugghh.

So first, this is an example of two conditional claims that might have allowed for some inference that someone, somehow failed to draw. Some hopeful readers might believe that the new research on genius outlines a way in which smart drugs might really show massive benefits. So thanks, Teti, you’ve provided an explanation for why drug use is the answer to our dreams…

However, it isn’t clear that it’s that simple. It might be that in the normal (un-drugged) case, increased concentration and hard work allow for genius by jointly producing some cognitive structure that later becomes a convenient shorthand when everyone else has to redo the entire mental process to reach the same end (I’m totally just guessing, but it sounds plausible). Think of this like a synergistic effect of hard work and increased concentration in the ordinary case. Now enter the user of smart drugs. It might be that when the same process is engaged in the person the synergy might not occur, perhaps because the smart drugs interfere with the memory required to construct these cognitive structures or screw up some other unobservable part of the process. In that case, you might be back to post number one where you end up as a junkie, not as a genius.

I still think it comes back to this. You don’t want to be the first person off the psycho-pharmacological boat. Sure, it could be really, really good, but it could also be really, really bad, and people tend to be better at forecasting optimistic outcomes than pessimistic ones. So take that into account during your fantasy for juicing yourself and becoming Isaac Newton. And also, you’re going to get almost all the same benefits a couple of years from now after a bunch of people fry their processors looking for the right cocktail. Why not just wait a couple of years until our friends at Pfizer refine the process (which I assure you they’re already doing btw…) and the FDA agrees that it’s safe to go back into the water?

Article by Trent Teti of Blueprint LSAT Preparation.