My First Cadaver has been live for just over a month now, and the feedback so far has been phenomenal.

This podcast features real-life stories told by med students, residents and practicing physicians “with warmth, honesty, and low doses of schadenfreude.”

Since a number of people have reached out wanting to know more and asking how they can listen, we wanted to point you in the right direction:

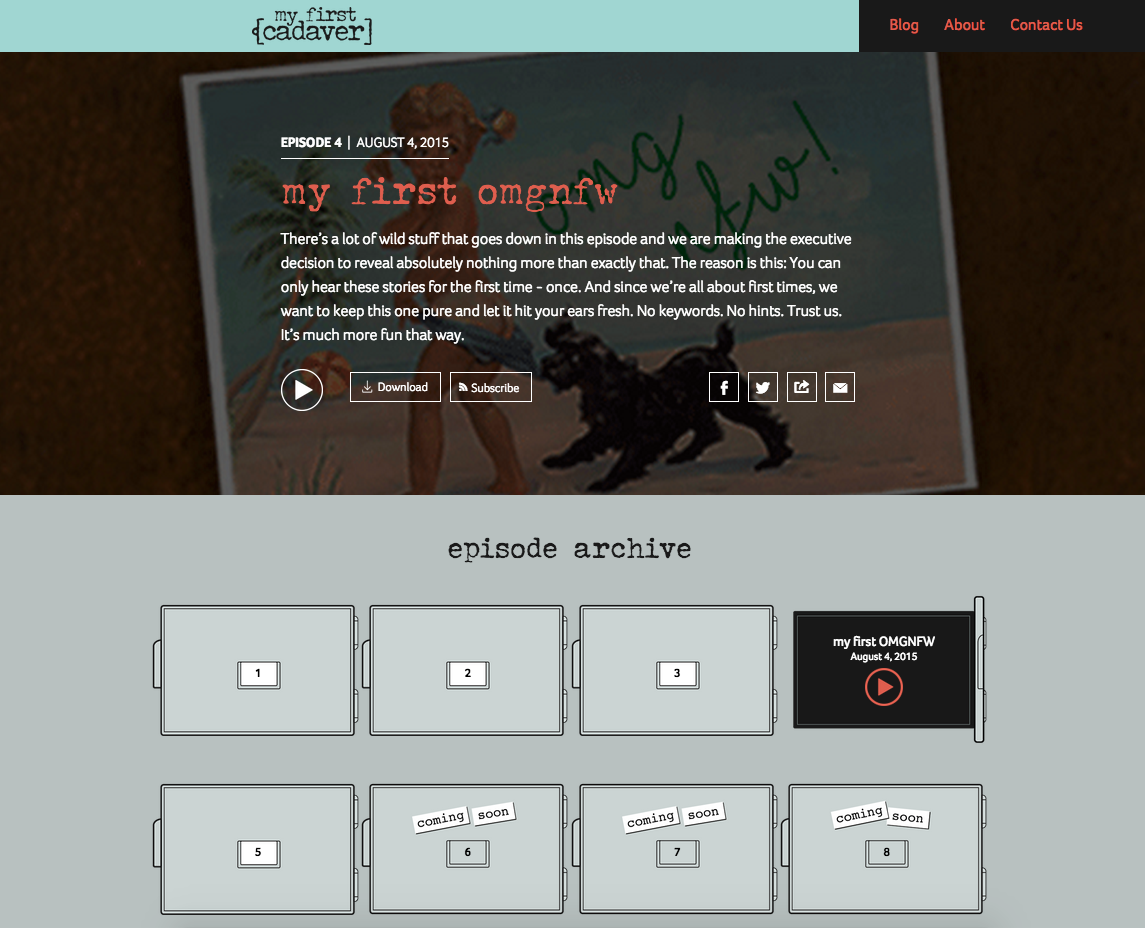

The first five episodes are now live, offered as both exclusive free video podcasts on the My First Cadaver website, as well as audio-only versions. We’re so proud to be sponsoring this podcast. Click on the buttons below to listen to a specific episode, or subscribe at one of the links at the bottom of this post.

“Our host, Faith Aeryn, investigates the death of her MD aspirations as she guides us through a series of first cadaver encounters with Christopher Showers and Doctors Daniel Maselli and Emma Husain.”

“Patients can be weird. Really weird. Here are some of the most uncomfortable situations in which med students and doctors can find themselves. With Christopher Showers and Doctors Michael Coords, Daniel Maselli, Sabina Bera and Christopher Carrubba.”

“Death ain’t for sissies, but neither is medicine. Still, how do you know when a patient is really dead — and where do you turn when you aren’t prepared to make the call? What does your response to patient loss say about you as a doctor? As a human being? This won’t be on a Shelf exam. This test is for your gut.”

“There’s a lot of wild stuff that goes down in this episode and we are making the executive decision to reveal absolutely nothing more than exactly that. The reason is this: You can only hear these stories for the first time – once. And since we’re all about first times, we want to keep this one pure and let it hit your ears fresh. No keywords. No hints. Trust us. It’s much more fun that way.”

“In this episode, doctors share the personal pathways that led them to medicine, particular specialties, and the kinds of questions that gave them their answers. With Doctors Michael Coords, Pranay Sinha, Haren Heller Dane, Emma Husain, Sarah Coates, Zina Semenovskaya and Nicholas Rowan.”

To listen to the audio-only versions of the podcast, choose any of the following, and be sure to subscribe/follow on these sites so you’ll be automatically updated when each new episode premieres:

And finally, if you have a story you want to share or a topic you’d like the My First Cadaver team to cover, get in touch with them here. After all, everybody’s gotta start somewhere.

(Don’t have time to listen right now? We’ve included the transcript from Episode 5 below!)

Episode 5 of the podcast “My First Cadaver” goes out to anyone in medical school, in their residencies, or working as practicing physicians. Below is the transcript of this episode:

MST AD: “My First Cadaver” is sponsored by Med School Tutors. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, infiltrate the USMLE and retrieve a high score from it’s fortified test center. MST has developed top secret tools to aid you in your quest. Personalized study schedules, comprehensive high yield review and GTM transmitters to connect you one on one with our highly trained exam crushing special agents. Oh yes, and this briefcase with a hidden flame thrower. Try to bring everything back in on piece this time. Let Med School Tutors be a part of your origin story. Together, we can save the world.

FAITH AERYN: Attention Grown-ups! Assuming we are all grown-ups, however reluctant, how did you know what you wanted to be when you did, eventually, inevitably, possibly somewhat regretfully, grow-up? I’m Faith Aeryn and you are listening to My First Cadaver. Considering that, in all likelihood, you are not Batman or a rockstar or playing center field for the New York Yankees — although maybe you are; I’m not here to judge — you probably changed your mind a few times over a couple of decades as you tried to figure out what you wanted to do or be, right? What exactly changed it? A fear of caves? An appalling lack of musical talent or athletic ability? Your mom? Or was it simply a sudden irrepressible desire to dedicate your life to science or medicine? Maybe it was all of the above. In this episode, we follow the unique paths of some of our favorite physicians. Dr. Michael Coords leads the way.

DR. MICHAEL COORDS: My older sister was the first person in my, I think the history of my family to go to college. My dad was a painter and laborer in New York City where he would paint like buildings and stuff and my mom was a medical assistant for a doctor’s office. Both my parents are very intelligent they just didn’t have the opportunities that I had. They didn’t have anyone pushing them to go to college. So when they finally had the opportunity to really push me they let me choose my own path but they were there to support me through it. From a very young age they I guess they wanted better for me? My mom used to take me around to houses and stuff, really run down, and be like, “Do you wanna live there when you grow up? Do you want to live there?” I’m like, “No!” “Well you better stay in school. You better go home and study.” She tried to scare me a little bit. From an early age I sort of thought I wanted to do medicine. I went into undergrad having it in the back of my mind. But it wasn’t really until maybe my second year in undergrad that I really decided that I wanted to do medicine. When I was applying to med school I actually didn’t think I was going to get in. I didn’t think that I was good enough for medical school. So when I did get into medical school I was like, “Ah crap. All these people are ridiculously smart. Somehow, I just happened to get by on the MCAT because I know physics and I know the biological sciences. My verbal score we won’t even talk about. So I got in but here I am thinking that all these people are absolutely amazing, coming from the best schools across the country, so I have to go home and study really hard every single night and really work my butt off to try to ya know I guess make people really think that I was on a similar level as them.

DR. PRANAY SINHA: I got into medicine because I really love Sherlock Holmes.

FA: That’s Doctor Pranay Sinha, an internal medicine resident and a graduate of the University of Virginia School of Medicine.

PS: I just look at a patient’s medicine list and I know the kind of things they struggle with. I can picture the person based on the kind of medications they take. I can pretty much anticipate the interview. I’m wrong sometimes, ya know, many times I can be wrong. Most of the times I get a lot of things right. I think that’s what’s amazing about this profession is it’s about studying human beings, that’s what we do. One of the things that I really got into is this concept of a narrative in medicine. Really as physicians we’re dealing with these different stories and so when you come to me as a physician I’m going to figure out which story you fit into and have I seen this story before and how does it play out and how can I change the narrative with my medicines or surgeries or whatever I have. So in that assessment section what I do, typically, is I give people a story. I say, “Well, you know, I think this is a lovely 82 year old lady who has dementia and so when she got a UTI five days ago she kind of got a little bit loopy and because of that she swallowed her food the wrong way and now she has this pneumonia which all of her labs are pointing us towards. So that is the story of this patient. And that is what I’ve seen my dad do. My father is a neuro physician and in turn my mother is a gynecologist so I saw them do this all my life and I thought this was the coolest thing on Earth. So that is pretty much what drove me to medicine was sort of this ability to observe and sort of create a narrative out of thin air. That was pretty cool.

DR. HAREN HELLER DANE: I, for some reason, at the age of four decided that I wanted to be a doctor.

FA: That’s Doctor Haren Heller Dane—an anesthesiologist and graduate of the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

HHD: My parents got me a little doctor kit and I loved playing with it and I guess I didn’t really know the concept of what it was exactly until I got a little older. For a period of time I wanted to be the first woman professional baseball player and then I went back to wanting to be a doctor again. By the time I wanted to be a doctor again I was in high school and I volunteered as an EMT at the rescue squad near our house in our neighborhood and I really really loved it. I really loved the idea of helping people. I know it sounds really really cliche but it’s true. I was always a helper and I really loved the idea of being there for people at their time of need. When I went into medical school I thought I wanted to be an obstetrician gynecologist and I wound up in a completely different field but I absolutely love it and I still feel like I’m helping people. And half the time they don’t even remember who their anesthesiologist was but for me it’s so rewarding because I just feel like at this particular part in their life they’re the most vulnerable, they need someone to take care of them, to take away their pain, to make sure they don’t remember it. The thing about anesthesia is it’s a lot of sort of medicine and surgery. You have to be able to diagnose what’s going on in an instant or at least have an idea of what’s going on in an instant and treat fast. You sort of think about the differential diagnoses like a medical doctor but you act quickly like a surgeon and I really loved it. Anesthesiologists are a good fun bunch of people. As you start talking to doctors I think you’re going to realize that there’s going to be like certain people that go into certain fields and they have a certain type of personality in each field. Anesthesiologists tend to be like the newspaper reader, coffee drinker, ya know little more relaxed. But still like, inside, a little anal about stuff too. You have to be a little anal to go into anesthesia but they’re also kind of funny and relaxed kinda people too.

PS: I think the way you select your specialty ends up being you end up finding your people in medicine. Pretty much on day one of medical school you can call most people and you know whether or not they’re going to surgery or non surgery and I’ve always decidedly been a non-surgeon. And on day one you can tell who are the surgeons and they tend to be a lot, kind of like on Scrubs, they tend to be a lot cooler. In general, maybe a little bit more cocky, a little bit more panache. So one of my first roommates, he’s now a general surgery resident and I met him on Day One like, “You’re going into surgery aren’t you?”and he’s like, “Yeah, how do you know that?” like, “There’s something about you.” and I’ve always been pretty classic internal medicine which is pretty geeky and nerdy. And even within medicine there are variations and I can speak within internal medicine there are stereotypes and you know the scary part about these stereotypes is that they’re largely correct. So there tend to be these people who are like Cardiologists tend to be kind of bro-ey people. They’re very smart but they also have very little patience for sort of long term — like this whole narrative thing I talked about, they have no patience for that. They sort of want to get to, they want to get to fixing things. They want to put stents in, they want to give the right meds, that’s what they want to do. GI people tend to be really cool and really funny. I think half of them go into GI just to be able to make poop jokes. Which is pretty good you know? They’ll come in and say, “I have a really shitty speciality.” and they’re right. They also tend to be more on the interventional side. They want to act, they don’t want to sit around doing long, sort of, work ups. Then the endocrinologists tend to be very cerebral people who think a lot. They really sort of things make sense for them. The geeks — heme onc people tend to be really smart. Really, really smart honestly but they tend to be also very caring people generally speaking and a very strong inclination towards basic sciences. Then I’ll talk about I.D. which is what I want to do, infectious disease. We tend to be really oddball people who like to have random pieces of knowledge floating around in our brains. Tend to be extremely liberal and kind of hipsterish and most of us tend to be into global health. Ultimately I choice I.D. because when I did that rotation I just felt like I was among friends. They got my jokes, I got theirs, we went to the same kind of things and we talked for hours about which is, if you don’t know that, it’s a fungus that you get when you have an accidental drowning. Nobody cares about that apart from I.D. physicians and nobody should really. The fact that they were equally interested in that made me feel really happy and aglow inside. And so that’s kind of how I made my decision and I think that’s how a lot of people do similar things. They find their people.

DR. EMMA HUSAIN: It’s interesting because I think it’s a combination of two things. One is, you like what you’re good at, you’re good at what you like and that’s science and math and stuff like that.

FA: That’s Dr. Emma Husain.

EH: But then one of the reasons that I am good at science and math is because I have an Indian dad, it’s like completely cultural. Because you just can’t be a son or daughter of an Indian man, who will always be an engineer. My dad’s an engineer, his brother’s an engineer, my cousins are engineers. They’re all engineers and they all instill this severe math science training. So I think it’s actually very cultural more than it had anything to do with me but then at the point where I was old enough to make decisions I still wanted it. I wanted to conquer and know a big field of knowledge, I really liked that and I wanted to help people. I know that sounds cliche but I really did.

FA: I’d like to pause for a moment here to try to wrap my mind around something that has been perplexing me. I’ve heard countless physicians dismiss wanting to help people in almost exactly the same way:

EH: I wanted to help people. I know that sounds cliche.

FA: After Emma, Sarah Coates, and Haren Heller Dane did this as well, I asked them (in that order) to help me understand where this impulse comes from to dismiss what seems to be such a pure, instinctual calling.

EH: When we say we want to help people and that’s why we’ve become doctors, I may be speaking just for myself, but I feel like what we’re really saying is I want to have power over illness. I would like to be able to control something for the better. The only way to help people as an adult and also still be an adult and not just like a philanthropist; is to find a place of power and then act from there. That, I think, is where I might be having an epiphany here but I think that’s where all of this discord happens with us because we want power over illness and power over in a good way, right, we want to be a benevolent dictator over illness, we want that. But the whole first four years are an exercise in total powerlessness. You don’t even get to wear a real white coat you have to wear this little short white coat of shame that, ya know, a dunce cap and walk around in it. So the one thing that you’re trying to get, which is a form of power, is actually trickling away from you more than it’s coming to you. I think that’s the problem actually or at least I can see that in hindsight.

DR. SARAH COATES: I just think inside of our heads we’re all battling what a socially acceptable reason to do something is and what a less than noble reason is to do something. I think that when you say something like, “I got into medicine because I want to help people,” a lot of non-medical people, first of all, will take something like that and they’ll think, “Well that’s an awfully long road to go toward a pretty lucrative profession if you truly want to help people.” There are so many ways to improve people’s health that are not being a doctor. I think only ten percent of people’s health and wellbeing can be tied back to their interactions with physicians. Whereas a lot of it is public health and community things like nutrition and fitness and so I think that a lot of people become doctors without realizing it because they want to be respected and they want to feel like they matter. “I want to help people” is socially acceptable and “I want to feel like I matter” is not really a nice way to say why I want to do what I want to do. So I think that it’s not that we just want to help people I think that it’s that we want to help people and we want to call the shots. We want to be responsible for when things get better and we want to be in charge when hard decisions have to be made. A lot of that comes down to wanting to be respected. We’re leader types, we’re caregivers.

HHD: I do think it comes from, at least for me, it does come from a family that we’re helpers. My mom’s a school teacher, my dad has always been one of those people that would give the shirt off his back to someone else. I don’t know if that is part of temperament, ya know, something you’re born with or if it’s something learned when you’re really little. But it is I do believe that there’s a pure feeling to it because I see it in my four year old, ya know, that she’s a helper. That’s the doctor, right there, she’s a helper. She goes out of her way to make people try to feel better. She’ll give a hug to her brother if something’s wrong, she’s the one that tries to fix things if it’s broken. You can already see at such a young age yeah. Most people that go into medicine go into it to help people and to be part of that it’s just the next thing to god. It’s an honor, it’s an honor to just be part of that.

FA: Let’s go to Doctor Zina Semenovskaya, a graduate of the Weill Cornell Medical College.

DR. ZINA SEMENOVSKAYA: I actually became an EMT because there was a boy, life’s always about a boy. There was a boy in my high school who was two years older than me and he was a volunteer EMT at the ambulance there. You can be a volunteer EMT from the age of 16 and he always had this pager that was always going off and was telling us stories about coming to car accidents scenes and helping evacuate patients. It was very exciting and dramatic especially for a 16 year old and I was living in a suburban New Jersey town. As soon as I turned 16 I volunteered to be an EMT. You do a class in order to get your license, it took about six months part time to complete the class and I just loved it. It was so much fun and it felt really real so it was very exciting and I really liked it and I found that I was good at it and I was good in stressful situations. Then I actually ended up shadowing some doctors and I thought that that was really really cool. I liked the idea of being the person in charge, ya know, making decisions, running everything, knowing what to do in all these different circumstances. So I decided to be pre-med in college and I guess emergency medicine was basically inevitable because when you start out as an emergency medical technician what you do is basically, you know, emergency medicine in the field and then all of the doctors you interact with essentially are emergency physicians because those are the ones who are in the emergency rooms. They’re the first ones that you see when you get there and the first ones to asses and take care of patients. I just loved it and I loved the variety of things that you do. One minute you’re taking care of a pregnant patient whose bleeding, the next minute you’re taking care of a heart attack, then it’s a patient with a gunshot wound, then there’s a little baby with a fever. You know what to do in all of the circumstances. You’re not going to be the person that takes them to the operating room, you’re not going to be the specialist that sees them in two weeks for their follow up. You’re the one that’s there that can make sure that they’re not going to die from whatever is going on. You can alleviate their pain, you can make the initial diagnosis, start the work up and then make them feel better and then ultimately get them to where they need to go. It’s really exciting in that way, it’s really intense. It can also be really exhausting and draining but I really like it.

DR. NICHOLAS ROWAN: Probably my favorite story is how I got into the field.

FA: That’s Doctor Nicholas Rowan, a graduate of the UMDNJ Medical School.

NR: So I went to Undergraduate at Pepperdine which is conveniently situated on the beach in Malibu and it allowed me to partake daily in one of my favorite hobbies which was surfing. It was a really good day. The waves were really up and I went out and after being out in the water for about an hour I ended up taking a surfboard to the face while riding a wave and I broke both my eye sockets and my nose pretty nicely and cut my face open and had to be rushed to the hospital. Two days later I was having my orbits repaired and my nose set back into place and my face sewn up and if you look at my face today you can’t tell that I had any of that done. I think that is the coolest thing ever and so when I’m in the emergency department at three in the morning and somebody is, you know, they’re hysterical. They’ve gotten into a car accident they’ve gotten hit, they’ve had whatever and they’re really upset and they think their face is never going to look normal ever again. They see in the mirror what they look right now and yeah don’t get me wrong it does look awful but then I can say to them as their physician I can say, “Well ya know what? Listen, I had from eye socket to eye socket just as messed up as you did and you can look at my face,” if you can open your eyes, if their eyes aren’t swollen shut or whatever, but and I can say, “You know, you’re gonna be fine. You’re going to be absolutely fine.”

FA: There must be a moment in our internal search histories where we hit upon something that made us think or feel a certain way that we want to think or feel again, so we adjust our keywords, delve a little deeper and realize, “Maybe I could do this thing, this thing that makes me think or feel this way, for the rest of my life and I could be happy.” That thing could make us feel powerful or smart, or make us think about solving puzzles or helping people. But that thing propelling us into forward motion is also uncovering our deepest core values. Like the right pair of prescription lenses or contacts in a mirror, this thing can help us better see ourselves for who we really are, as well as provide us with the vision to see who we can become. But if you can be Batman, always be Batman.

Thank you to Doctors Michael Coords, Pranay Sinha, Haren Heller Dane, Emma Husain, Sarah Coates, Zina Semenovskaya and Nicholas Rowan.

The My First Cadaver Team

Papa Claire Music & Compulsion Music

Our Nerf-blasting friends at Salted Stone

And special thanks to Robert Meekins who is NOT a doctor.

Do you have a story you want to share or a topic you want to hear about? Get in touch with us at myfirstcadaver.com.

Stay tuned for Episode 6. And remember, don’t try to fend off a troupe of monkeys from your balcony, or you could become someone’s first cadaver.

PS: And when you think about it, the physical exam is such a classic physician tool. You can’t imagine a physician who can’t use a stethoscope even though there are plenty of them. They’re called Ophthalmologists and Radiation Oncologists also and Radiologists they can not use a stethoscope.

MC: I didn’t have a stethoscope or anything like that. I mean what am I gonna do with it? Pretend to listen to lung sounds? Eh I never knew how to use one of those things.

MST AD:This episode of “My First Cadaver” was sponsored by Med School Tutors. Were your exam scores so high the KGB opened a file on you? Consider joining our team of elite tutoring agents, who like their drinks shaken not stirred. Use your unrivaled knowledge, discipline and skill to help aspiring double O’s their license to practice and be paid handsomely in return. We’ll need all the help we can get to crush the forces of USMLE, COMLEX, MCAT and SPECTRE. Let Med School Tutors be a part of your origin story. Together, we can save the world.